USP9X

| USP9X | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | USP9X, DFFRX, FAF, FAM, MRX99, MRXS99F, ubiquitin specific peptidase 9, X-linked, ubiquitin specific peptidase 9 X-linked, XLID99 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 300072; MGI: 894681; HomoloGene: 3418; GeneCards: USP9X; OMA:USP9X - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Probable ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase FAF-X is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the USP9X gene.[5][6]

Function

This gene is a member of the peptidase C19 family and encodes a protein that is similar to ubiquitin-specific proteases. Though this gene is located on the X chromosome, it escapes X-inactivation.

Depletion of USP9X from two-cell mouse embryos halts blastocyst development and results in slower blastomere cleavage rate, impaired cell adhesion and a loss of cell polarity. It has also been implicated that USP9X is likely to influence developmental processes through signaling pathways of Notch, Wnt, EGF, and mTOR. USP9X has been recognized in studies of mouse and human stem cells involving embryonic, neural and hematopoietic stem cells.[7] High expression is retained in undifferentiated progenitor and stem cells and decreases as differentiation continues. USP9X is a protein-coding gene that has been implicated either directly through mutations or indirectly in a number of neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. Three mutations have been connected with X-linked intellectual disability through disrupted neuronal growth and cell migration. Neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and Huntington's disease, have also been linked to USP9X. Specifically, USP9X has been implicated in the regulation of the phosphorylation and expression of the microtule-associated protein tau, which forms pathological aggregates in Alzheimer's and other tauopathies.[8] Scientists have generated a knockout model where they isolated hippocampal neurons from an USP9X-knockout male mouse, which showed a 43% reduction in axonal length and arborization compared to wild type.[9]

Interactions

USP9X has been shown to interact with:

USP9X Syndrome

Variants of the USP9X gene have been found to cause a neurodevelopmental USP9X syndrome in both males and females. USP9X is strongly evolutionarily conserved in humans and is intolerant to variation. This is due to the important role of the USP9X enzyme, which reverses protein ubiquitylation, thereby decreasing the enzymatic degradation and increasing the longevity of those proteins.[15] Being on the X chromosome, USP9X syndrome manifests differently in females compared to males. In females, loss of function variations in one copy of the gene results in haploinsufficiency. This is because USP9X escapes the usually-protective process of X-inactivation. As a result, even “carrier” females exhibit the syndrome.

Variants found in females with USP9X syndrome include whole or partial deletions of one copy of the USP9X gene, as well as mis-sense mutations or small in-frame deletion mutations.[15] Symptoms in females include intellectual disability, facial dysmorphia, and language impairment. Less common symptoms include short stature, scoliosis, polydactyly, and changes to dentition.[16] Females have a wider range of symptoms than males, likely due to their wider variety of USP9X gene variants compared to males. Other symptoms sometimes found in females but rarely or never in males include hip dysplasia, heart dysmorphia, hearing problems and abnormal skin pigmentation.[15]

USP9X variants seen in surviving males cause loss of function in brain-specific processes only, since total loss of function of this gene is fatal in the embryonic stage. Males are hemizygous for this gene because they possess only one X chromosome. Symptoms seen in affected males include intellectual disability, problems with language, speech, behaviour and sight, and facial dysmorphia. Specific brain abnormalities include white matter disturbances, a thin corpus callosum, and widened ventricles.[17]

References

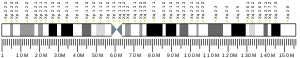

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000124486 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000031010 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Jones MH, Furlong RA, Burkin H, Chalmers IJ, Brown GM, Khwaja O, Affara NA (1996). "The Drosophila developmental gene fat facets has a human homologue in Xp11.4 which escapes X-inactivation and has related sequences on Yq11.2". Hum. Mol. Genet. 5 (11): 1695–701. doi:10.1093/hmg/5.11.1695. PMID 8922996.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: USP9X ubiquitin specific peptidase 9, X-linked".

- ^ Murtaza M, Jolly LA, Gecz J, Wood SA (2015-01-01). "La FAM fatale: USP9X in development and disease". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 72 (11): 2075–2089. doi:10.1007/s00018-015-1851-0. ISSN 1420-682X. PMC 4427618. PMID 25672900.

- ^ Köglsberger S, Cordero-Maldonado ML, Antony P, Forster JI, Garcia P, Buttini M, Crawford A, Glaab E (2016-12-01). "Gender-Specific Expression of Ubiquitin-Specific Peptidase 9 Modulates Tau Expression and Phosphorylation: Possible Implications for Tauopathies". Molecular Neurobiology. 54 (10): 7979–7993. doi:10.1007/s12035-016-0299-z. PMC 5684262. PMID 27878758.

- ^ "OMIM Entry - * 300072 - UBIQUITIN-SPECIFIC PROTEASE 9, X-LINKED; USP9X". www.omim.org. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- ^ a b Taya S, Yamamoto T, Kanai-Azuma M, Wood SA, Kaibuchi K (Dec 1999). "The deubiquitinating enzyme Fam interacts with and stabilizes beta-catenin". Genes Cells. 4 (12): 757–67. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00297.x. PMID 10620020. S2CID 85747886.

- ^ a b Al-Hakim AK, Zagorska A, Chapman L, Deak M, Peggie M, Alessi DR (Apr 2008). "Control of AMPK-related kinases by USP9X and atypical Lys(29)/Lys(33)-linked polyubiquitin chains" (PDF). Biochem. J. 411 (2): 249–60. doi:10.1042/BJ20080067. PMID 18254724. S2CID 13038944.

- ^ Taya S, Yamamoto T, Kano K, Kawano Y, Iwamatsu A, Tsuchiya T, Tanaka K, Kanai-Azuma M, Wood SA, Mattick JS, Kaibuchi K (Aug 1998). "The Ras target AF-6 is a substrate of the fam deubiquitinating enzyme". J. Cell Biol. 142 (4): 1053–62. doi:10.1083/jcb.142.4.1053. PMC 2132865. PMID 9722616.

- ^ Wang S, Kollipara RK, Srivastava N, Li R, Ravindranathan P, Hernandez E, Freeman E, Humphries CG, Kapur P, Lotan Y, Fazli L, Gleave ME, Plymate SR, Raj GV, Hsieh JT, Kittler R (2014). "Ablation of the oncogenic transcription factor ERG by deubiquitinase inhibition in prostate cancer". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111 (11): 4251–6. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4251W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322198111. PMC 3964108. PMID 24591637.

- ^ Li X, Song N, Liu L, Liu X, Ding X, Song X, Yang S, Shan L, Zhou X (2017-03-31). "USP9X regulates centrosome duplication and promotes breast carcinogenesis". Nature Communications. 8: 14866. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814866L. doi:10.1038/ncomms14866. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5380967. PMID 28361952.

- ^ a b c Jolly LA, Parnell E, Gardner AE, Corbett MA, Pérez-Jurado LA, Shaw M, Lesca G, Keegan C, Schneider MC, Griffin E, Maier F, Kiss C, Guerin A, Crosby K, Rosenbaum K (2020-12-09). "Missense variant contribution to USP9X-female syndrome". npj Genomic Medicine. 5 (1): 53. doi:10.1038/s41525-020-00162-9. ISSN 2056-7944. PMC 7725775. PMID 33298948.

- ^ "USP9X". Simons Searchlight. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

- ^ Johnson BV, Kumar R, Oishi S, Alexander S, Kasherman M, Vega MS, Ivancevic A, Gardner A, Domingo D, Corbett M, Parnell E, Yoon S, Oh T, Lines M, Lefroy H (2020-01-15). "Partial loss of USP9X function leads to a male neurodevelopmental and behavioural disorder converging on TGFβ signalling". Biological Psychiatry. 87 (2): 100–112. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.05.028. ISSN 0006-3223. PMC 6925349. PMID 31443933.

Further reading

- D'Andrea A, Pellman D (1998). "Deubiquitinating enzymes: a new class of biological regulators". Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 33 (5): 337–52. doi:10.1080/10409239891204251. PMID 9827704.

- Andersson B, Wentland MA, Ricafrente JY, Liu W, Gibbs RA (1996). "A "double adaptor" method for improved shotgun library construction". Anal. Biochem. 236 (1): 107–13. doi:10.1006/abio.1996.0138. PMID 8619474.

- Yu W, Andersson B, Worley KC, Muzny DM, Ding Y, Liu W, Ricafrente JY, Wentland MA, Lennon G, Gibbs RA (1997). "Large-scale concatenation cDNA sequencing". Genome Res. 7 (4): 353–8. doi:10.1101/gr.7.4.353. PMC 139146. PMID 9110174.

- Dias Neto E, Correa RG, Verjovski-Almeida S, Briones MR, Nagai MA, da Silva W, Zago MA, Bordin S, Costa FF, Goldman GH, Carvalho AF, Matsukuma A, Baia GS, Simpson DH, Brunstein A, de Oliveira PS, Bucher P, Jongeneel CV, O'Hare MJ, Soares F, Brentani RR, Reis LF, de Souza SJ, Simpson AJ (2000). "Shotgun sequencing of the human transcriptome with ORF expressed sequence tags". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (7): 3491–6. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.3491D. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.7.3491. PMC 16267. PMID 10737800.

- Noma T, Kanai Y, Kanai-Azuma M, Ishii M, Fujisawa M, Kurohmaru M, Kawakami H, Wood SA, Hayashi Y (2002). "Stage- and sex-dependent expressions of Usp9x, an X-linked mouse ortholog of Drosophila Fat facets, during gonadal development and oogenesis in mice". Gene Expr. Patterns. 2 (1–2): 87–91. doi:10.1016/S0925-4773(02)00290-3. PMID 12617843.

- Murray RZ, Jolly LA, Wood SA (2004). "The FAM deubiquitylating enzyme localizes to multiple points of protein trafficking in epithelia, where it associates with E-cadherin and beta-catenin". Mol. Biol. Cell. 15 (4): 1591–9. doi:10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0630. PMC 379258. PMID 14742711.

- Bouwmeester T, Bauch A, Ruffner H, Angrand PO, Bergamini G, Croughton K, Cruciat C, Eberhard D, Gagneur J, Ghidelli S, Hopf C, Huhse B, Mangano R, Michon AM, Schirle M, Schlegl J, Schwab M, Stein MA, Bauer A, Casari G, Drewes G, Gavin AC, Jackson DB, Joberty G, Neubauer G, Rick J, Kuster B, Superti-Furga G (2004). "A physical and functional map of the human TNF-alpha/NF-kappa B signal transduction pathway". Nat. Cell Biol. 6 (2): 97–105. doi:10.1038/ncb1086. PMID 14743216. S2CID 11683986.

- Fu GK, Wang JT, Yang J, Au-Young J, Stuve LL (2004). "Circular rapid amplification of cDNA ends for high-throughput extension cloning of partial genes". Genomics. 84 (1): 205–10. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.01.011. PMID 15203218.

- Rush J, Moritz A, Lee KA, Guo A, Goss VL, Spek EJ, Zhang H, Zha XM, Polakiewicz RD, Comb MJ (2005). "Immunoaffinity profiling of tyrosine phosphorylation in cancer cells". Nat. Biotechnol. 23 (1): 94–101. doi:10.1038/nbt1046. PMID 15592455. S2CID 7200157.

- Al-Hakim AK, Göransson O, Deak M, Toth R, Campbell DG, Morrice NA, Prescott AR, Alessi DR (2005). "14-3-3 cooperates with LKB1 to regulate the activity and localization of QSK and SIK". J. Cell Sci. 118 (Pt 23): 5661–73. doi:10.1242/jcs.02670. PMID 16306228. S2CID 17404931.

- Kimura K, Wakamatsu A, Suzuki Y, Ota T, Nishikawa T, Yamashita R, Yamamoto J, Sekine M, Tsuritani K, Wakaguri H, Ishii S, Sugiyama T, Saito K, Isono Y, Irie R, Kushida N, Yoneyama T, Otsuka R, Kanda K, Yokoi T, Kondo H, Wagatsuma M, Murakawa K, Ishida S, Ishibashi T, Takahashi-Fujii A, Tanase T, Nagai K, Kikuchi H, Nakai K, Isogai T, Sugano S (2006). "Diversification of transcriptional modulation: large-scale identification and characterization of putative alternative promoters of human genes". Genome Res. 16 (1): 55–65. doi:10.1101/gr.4039406. PMC 1356129. PMID 16344560.

- Beausoleil SA, Villén J, Gerber SA, Rush J, Gygi SP (2006). "A probability-based approach for high-throughput protein phosphorylation analysis and site localization". Nat. Biotechnol. 24 (10): 1285–92. doi:10.1038/nbt1240. PMID 16964243. S2CID 14294292.

- Mouchantaf R, Azakir BA, McPherson PS, Millard SM, Wood SA, Angers A (2006). "The ubiquitin ligase itch is auto-ubiquitylated in vivo and in vitro but is protected from degradation by interacting with the deubiquitylating enzyme FAM/USP9X" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 281 (50): 38738–47. doi:10.1074/jbc.M605959200. PMID 17038327.

- Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M (2006). "Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks". Cell. 127 (3): 635–48. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. PMID 17081983.